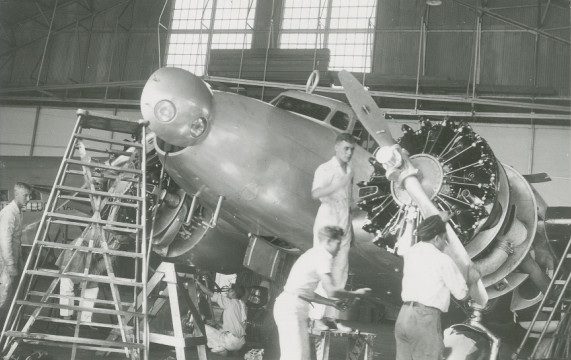

24 June 1943: At 12:33 p.m., Lieutenant Colonel William Randolph Lovelace II, M.D., Medical Corps, United States Army, made a record-setting parachute jump from a Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress over Ephrata, Washington, while testing high-altitude oxygen equipment. The altitude was 40,200 feet (12,253 meters). This was his first parachute jump.

Dr. Lovelace returned to Earth after a 23 minute, 51 second descent. This was the highest altitude parachute jump made up to that time.

Lovelace used a Type T-5 back-pack parachute which was opened by a static line attached to the bomber. The shock of the sudden opening of the 28 foot (8.5 meters) diameter parachute caused Lovelace to lose consciousness. He came to at about 30,000 feet (9,144 meters).

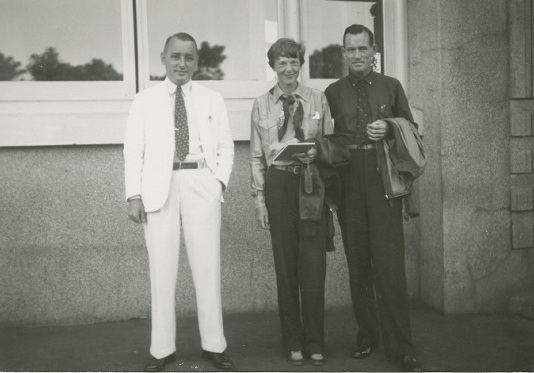

“On active duty with the Army Air Corps as a colonel during World War II, Lovelace used himself as a test subject in further experiments on the problems of high-altitude escape and parachuting. On June 24, 1943, he made his first parachute jump, bailing out of an aircraft 40,200 feet [12,253 meters] above Washington State. Although he was knocked unconscious by the opening shock of the parachute at the high altitude, and his hand was frostbitten when one of his gloves was torn away, valuable data was gained from his ordeal and he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for the experiment. He returned to private practice after the war, and in 1947, founded the Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico.”

—International Space Hall of Fame at the New Mexico Museum of Space History

© 2017, Bryan R. Swopes