27 June 1937: Leg 26. Bandoeng, Java, to Koepang, Timor, Dutch East Indies.

“Finally on Sunday, June 27, we left Bandoeng. I had hoped to be able to keep on to Port Darwin on the northern coast of Australia, but the penalty for flying east is losing hours. Depending on the distance covered, each day is shortened and one has to be careful to keep the corrected sunset time in mind so as not to be caught out after dark. For instance, between Koepang and Australia there is a loss of one and a half hours. So, as our landing in Koepang five hours after our start was too late to permit safely carrying on to Darwin that day, we settled down overnight in the pleasant Government rest house, planning to leave the airport at our conventional departure time, dawn. Koepang is on the southerly tip of the island of Timor, the last outpost of the archipelago of Holland-owned islands which string out southeasterly from Sumatra. As a matter of fact half of Timor is not under Dutch but Portuguese control. In the flight from Bandoeng the first 400 miles was over the lovely garden-land of Java. Then we looked down briefly upon Bali, much photographed island of quaint dancers, lovely costumes, lovelier natives, a well-publicized earthy heaven of dulce far niente. Thence we passed over Sujmbawa island, skirted Flores, and cut across a broad arm of the Arafura Sea toward Timor.

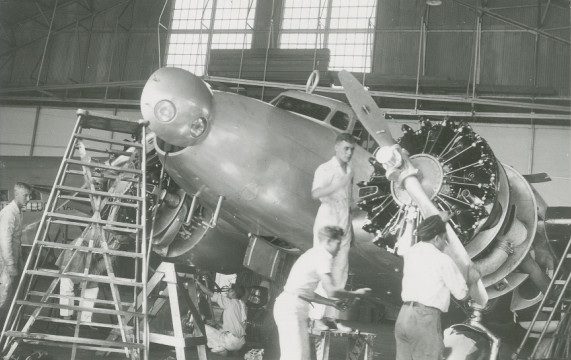

“As we left Java the geographic characteristics began to change. From lush tropics the countryside became progressively arid. The appearance of Timor itself is vastly different from that of Java. The climate is very dry, the trees and vegetation sparse. There was little or no cultivation in the open spaces around the airport, the surface of which was grass, long, dry and undulating in a strong wind when we arrived. The field, surrounded by a stout stone fence to keep out roaming wild pigs, we found to be a very good natural landing place. There were no facilities except a little shed for storing fuel, consequently we had to stake down our Electra and bundle it up for the night with engine and propeller covers. That is an all-important job carefully done; no pilot could sleep peacefully without knowing that his plane was well cared for. Our work much amused the natives from a near-by village. When we had to turn the craft’s nose into the wind, all the men willingly and noisily helped us push it as desired.”

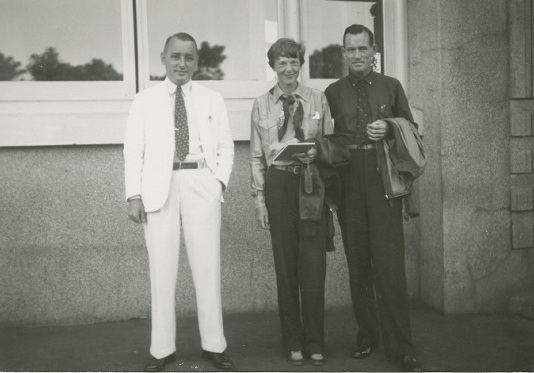

—Amelia Earhart

© 2019, Bryan R. Swopes